N E W M E X I C O H I S T O R I C A L T E X T I L E R E S O U R C E S

Please contact your proposed place or event to confirm.

For additions, edits, and whatknots contact the Editor

A HISTORIC OVERVIEW

Read this article by Molly Elkind:

Wednesday, October 3, 2018: Pueblo textiles: a weaver’s education continues mollyelkindtalkingtextiles.blogspot.com/2018/10/pueblo-textiles-weavers-education

Wednesday, October 3, 2018: Pueblo textiles: a weaver’s education continues mollyelkindtalkingtextiles.blogspot.com/2018/10/pueblo-textiles-weavers-education

Fiber has a long history in New Mexico. From early times natural fibers, from the immediate environment, were used to fulfill many daily utilitarian needs from sandals to baskets to rugs and blankets. Natural dyes were experimented with and used with growing success. Early fibers were yucca and willow. Early dyes came from plants, berries, bark, roots and flowers and leaves. These plants produced a range of color from browns and yellows while minerals provided reds, yellows, and black.

The people of early New Mexico were not isolated, but traveled and traded with their surrounding geography, borrowing and sharing resources, plant and other materials, techniques and culture. Cotton was introduced around 1000 and spread along the Rio Grande Valley. The portable, upright Pueblo loom and the back strap loom were invented and widely used.

The arrival of the Spanish in the early 1500s brought tremendous change – soldiers, settlers, priests, and servants, and thousands of animals. They brought the sturdy Churro sheep, a highly adaptable animal with two distinct layers or coats of wool. The outer coat produces a long, coarse fiber, while the under coat is shorter, soft and flexible. Thru raiding and barter, the Navajo acquired sheep for themselves and became a herding society. They acquired Spanish looms thru the settlers.

For nearly 300 years, until the coming of traders over the Santa Fe Trail in the 19th century, Churro sheep wool was the foundation of many Native, Spanish, and Mexican textiles. Spanish colonists also brought the horizontal European treadle or floor loom. In 1638 the Spanish set up a textile workshop in Santa Fe weaving on Spanish treadle looms. They produced the Serape or wearing blanket under the direction of the Spanish. The Pueblo weavers who had taken refuge with the Navajo (Diné) brought the techniques to the women who cared for the sheep

The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 virtually halted the growing textile industry. By 1694 the Spanish Reconquest reestablished the Colonial enforced labor textile industry. By 1790 large sheep herds existed around the Albuquerque area accompanied with a substantial population of weavers. In 1807 the Spanish government sent master weavers, Juan and Ignacio Bazán, to Santa Fe to teach technical skills and improve the industry. They bring the magnificent Saltillo serape designs. Rio Grande design elements still today reflect the legacy of the Bazån brothers. In 1821 Mexico became independent from Spain. Trade flourished along the Santa Fe Trail. The arrival of the railroad in 1879 brought in goods, yarn and synthetic dyes. The Navajo established Trading Posts to fill the ever increasing demand for their weavings.

At Bosque Redondo - the imprisonment of much of the Navajo in the 1860's resulted in a decimated population when they returned to their land five years later and were provided with yarns and synthetic dies. The Spanish blankets have influenced Navajo designs, resulting in experimental pieces such as eye-dazzlers--distinctive textiles with complex serrated patterns and vibrating color schemes.

Only small Spanish communities in the north, such as Chimayó continue the Rio Grande weaving tradition. Pueblo weavings are used only for ceremonial purposes.

The people of early New Mexico were not isolated, but traveled and traded with their surrounding geography, borrowing and sharing resources, plant and other materials, techniques and culture. Cotton was introduced around 1000 and spread along the Rio Grande Valley. The portable, upright Pueblo loom and the back strap loom were invented and widely used.

The arrival of the Spanish in the early 1500s brought tremendous change – soldiers, settlers, priests, and servants, and thousands of animals. They brought the sturdy Churro sheep, a highly adaptable animal with two distinct layers or coats of wool. The outer coat produces a long, coarse fiber, while the under coat is shorter, soft and flexible. Thru raiding and barter, the Navajo acquired sheep for themselves and became a herding society. They acquired Spanish looms thru the settlers.

For nearly 300 years, until the coming of traders over the Santa Fe Trail in the 19th century, Churro sheep wool was the foundation of many Native, Spanish, and Mexican textiles. Spanish colonists also brought the horizontal European treadle or floor loom. In 1638 the Spanish set up a textile workshop in Santa Fe weaving on Spanish treadle looms. They produced the Serape or wearing blanket under the direction of the Spanish. The Pueblo weavers who had taken refuge with the Navajo (Diné) brought the techniques to the women who cared for the sheep

The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 virtually halted the growing textile industry. By 1694 the Spanish Reconquest reestablished the Colonial enforced labor textile industry. By 1790 large sheep herds existed around the Albuquerque area accompanied with a substantial population of weavers. In 1807 the Spanish government sent master weavers, Juan and Ignacio Bazán, to Santa Fe to teach technical skills and improve the industry. They bring the magnificent Saltillo serape designs. Rio Grande design elements still today reflect the legacy of the Bazån brothers. In 1821 Mexico became independent from Spain. Trade flourished along the Santa Fe Trail. The arrival of the railroad in 1879 brought in goods, yarn and synthetic dyes. The Navajo established Trading Posts to fill the ever increasing demand for their weavings.

At Bosque Redondo - the imprisonment of much of the Navajo in the 1860's resulted in a decimated population when they returned to their land five years later and were provided with yarns and synthetic dies. The Spanish blankets have influenced Navajo designs, resulting in experimental pieces such as eye-dazzlers--distinctive textiles with complex serrated patterns and vibrating color schemes.

Only small Spanish communities in the north, such as Chimayó continue the Rio Grande weaving tradition. Pueblo weavings are used only for ceremonial purposes.

IRVIN, LISA & EMILY TRUJILLO

Chimayo Weavers –

Centinela Traditional Arts

Chimayo

Chimayo Weavers –

Centinela Traditional Arts

Chimayo

|

www.chimayoweavers.com

"Eight Generations" Located in Chimayo, New Mexico, on the "High Road to Taos" Address: Centinela Traditional Arts, 946 State Road 76, Chimayo, NM 87522 Phone: (505)351-2180 Email: [email protected] |

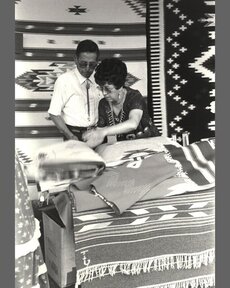

1987 picture of Irvin's parents

Jake & Belle Trujillo |

|

Irvin Trujillo

Collection Smithsonian American Art Museum ************

|

Lisa Trujillo

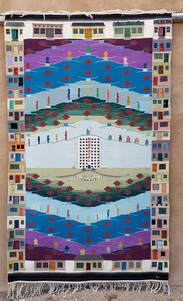

"19, 20, 21" To be Exhibited at the Museum of International Folk Art in the Gallery of Conscience |

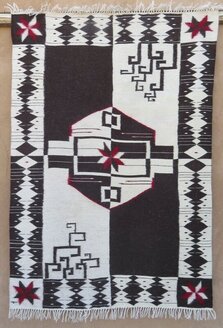

"Maniac," or "Maníaco"

By Emily Trujillo Honorable Mention at Spanish Market 2022 40"x60" Trampas Vallero, made of Two 20"x 60" tapestries, sewn together. All churro yarn from Emily's Aunt's sheep with a touch of cochineal dye. |

COLCHA EMBROIDERY - A REVIVAL

Colcha means “bedcover” in Spanish. This style of needlework was created by Colonial settlements

in northern New Mexico. Colcha embroidery has a wonderful history and revival.

The stitch that became known as “colcha” was a self-couching stitch.

in northern New Mexico. Colcha embroidery has a wonderful history and revival.

The stitch that became known as “colcha” was a self-couching stitch.

The colcha stitch was free-form and flowing. It was perfect for large motifs as well as finer details. This technique also maximizes the thread usage, which is important since most of the earlier stitching was done over the entire surface of the base fabric. The original base fabric was called “sabanilla”, a loosely-woven wool fabric with a 12- to 22-thread count. Colors were dictated by what was available. Sheep provided the wool in white, brown, and black. Dyes from plants provided green, yellow, and peach colored yarns. There was also a rare blue indigo and a red cochineal, made from crushed cactus bugs.

Industrialization brought commercially-made goods. Tighter woven cotton fabrics replaced the woven wool strips. The original yarns were also replaced by spun yarn that had a consistent size and twist. The overall designs were no longer needed to cover the loosely-woven patchwork strips. In time, even the handwork was abandoned to the modern finished products. The original embroidery had almost been forgotten except for museum exhibits.

Industrialization brought commercially-made goods. Tighter woven cotton fabrics replaced the woven wool strips. The original yarns were also replaced by spun yarn that had a consistent size and twist. The overall designs were no longer needed to cover the loosely-woven patchwork strips. In time, even the handwork was abandoned to the modern finished products. The original embroidery had almost been forgotten except for museum exhibits.

The first revival began in the 1930’s in Carson, New Mexico. There was a salvage operation that took old colcha pieces and tried to repair them – it brought the heritage stitching back.

The middle 1970’s, the Museum of International Folk Art reached out to women in the region with the Villenueva project,The museum sponsored workshops teaching colcha embroidery. Women were encourged to stitch pictorial projects based on their daily lives. Following in the 1980’s, Colcha embroidery played a large part in the revitalization of the San Luis Valley. Father Patricio Valdez created The Sewing Circle, which was predominantly Hispanic women.

The middle 1970’s, the Museum of International Folk Art reached out to women in the region with the Villenueva project,The museum sponsored workshops teaching colcha embroidery. Women were encourged to stitch pictorial projects based on their daily lives. Following in the 1980’s, Colcha embroidery played a large part in the revitalization of the San Luis Valley. Father Patricio Valdez created The Sewing Circle, which was predominantly Hispanic women.

|

EMBROIDERED HISTORY: COLCHAS AND THE STITCH THAT DEFINED A REGION

Sunday, June 2, 2019 to Sunday, November 10, 2019 HARWOOD MUSEUM - TAOS Hispanic Traditions Gallery Contact |

Visit the NMFAD Video Page to View

COLCHA CIRCLE: A STITCH IN NORTHERN NEW MEXICO CULTURE A documentary video produced by the Española Valley Fiber Arts Center (EVFAC) |